Editor's Note: This story contains details of self-harm. If you or someone you know is considering suicide or other acts of self-harm, please contact Colorado Crisis Services by calling 1-844-493-8255 or texting “TALK” to 38255 for free, confidential, and immediate support.

A Colorado eye doctor is criticizing the Food and Drug Administration's decision to stand by its policy of rejecting cornea donations from men who have sex with men.

That decision is based on guidance from a 30-year-old paper suggesting the possibility of HIV transfer through corneal tissue.

“I think their position is ridiculous and negligent,” said Dr. Michael Puente, a pediatric ophthalmologist at the University of Colorado and Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora. “It’s ridiculous that a policy still exists with no scientific evidence to support it.”

The 1994 report upon which the FDA relies came out at a time when there were no tests available to quickly detect the presence of HIV – tests that have been replaced by more current ones that can detect it within days, said Puente, 36.

“The reason I got involved in this was because no one else was speaking up about it,” he said. “And as an ophthalmologist who was very bothered by this policy and the harm that it was causing to blind people who were being denied surgery, I felt like I needed to speak up.”

He’s behind the online campaign, Legalize Gay Eyes which advocates for people to contact their state representatives and post on social media to change the policy. Puente said he has contacted U.S. Congressman Joe Neguse and tries to bring attention to the issue by sparking conversations whenever he can.

“I think we need to just keep having more and more people chime in, letting them know that we want to have a health care system that’s based on science and evidence from the 2020s, not the 1990s,” he said.

In 2019, while finishing his residency at CU Anschutz, he heard about an Iowa boy so badly bullied for being gay that he killed himself. His mother made sure her son could donate organs, but his corneas were rejected because he was gay.

“That story shocked me and made me angry that there was a policy in my field that seemed discriminatory,” he said.

Unable to find published research on the topic, he and colleagues did some themselves.

“We contacted every eye bank in the United States and Canada and asked them how many potential corneal donations did they have to turn away in one calendar year for no other reason than because the donor was gay,” he said.

In 2020, his findings were published in a six-page report in the Journal of the American Medical Association Ophthalmology, titled: Association of Federal Regulations in The United States and Canada With Potential Corneal Donation by Men Who Have Sex With Men, described on its title page as an “original investigation.”

“We estimated it was anywhere from 1,600 to 3,200 corneas every year” that were rejected, he said. Based on his research calculations indicating about 70,000 donations nationally in the US and Canada, he found that “about 4 percent of the total is being thrown away.”

Other countries don’t have the same restrictions, leading to the paper’s conclusion: “The FDA and Heath Canada should consider the example of other nations by shortening or eliminating their [men who have had sex with another man] deferral policies for corneal donation.”

Corneal donation provides not only sight or clearer vision to the recipient but also a sense of fulfillment through giving, an experience families of donors have said they receive. At the Rocky Mountain Lions Eye Bank near Puente’s office in Aurora, there is a display of photos taken by people whose sight was restored by a donation of a cornea coordinated through that eye bank, the only one in Colorado that also serves Wyoming.

Everett “Butch” Bashaw was one of the eye bank’s donors. The donation process proved moving for his daughter, who now lives in Aurora. Alisha Bashaw, a 42-year-old therapist, said that her father taught high school chemistry for decades in Michigan before retiring to Colorado. A lifelong scientist, he always wanted to donate a part of himself to the field when he died.

“He would say things like, ‘I’m gone, I don’t need it anymore, so I might as well help someone else and see whatever that can be used for,’” his daughter said.

In 2016, he died from a heart attack at 64, and she and the eye bank coordinated the donation of the front part of his eye, essential for clear vision sometimes described as its windshield. “The cornea acts as the eye's outermost lens. It functions like a window that controls and focuses the entry of light into the eye,” according to the website of Eye Associates of New Mexico. “The cornea contributes between 65-75 percent of the eye's total focusing power” by refracting light entering the eye.

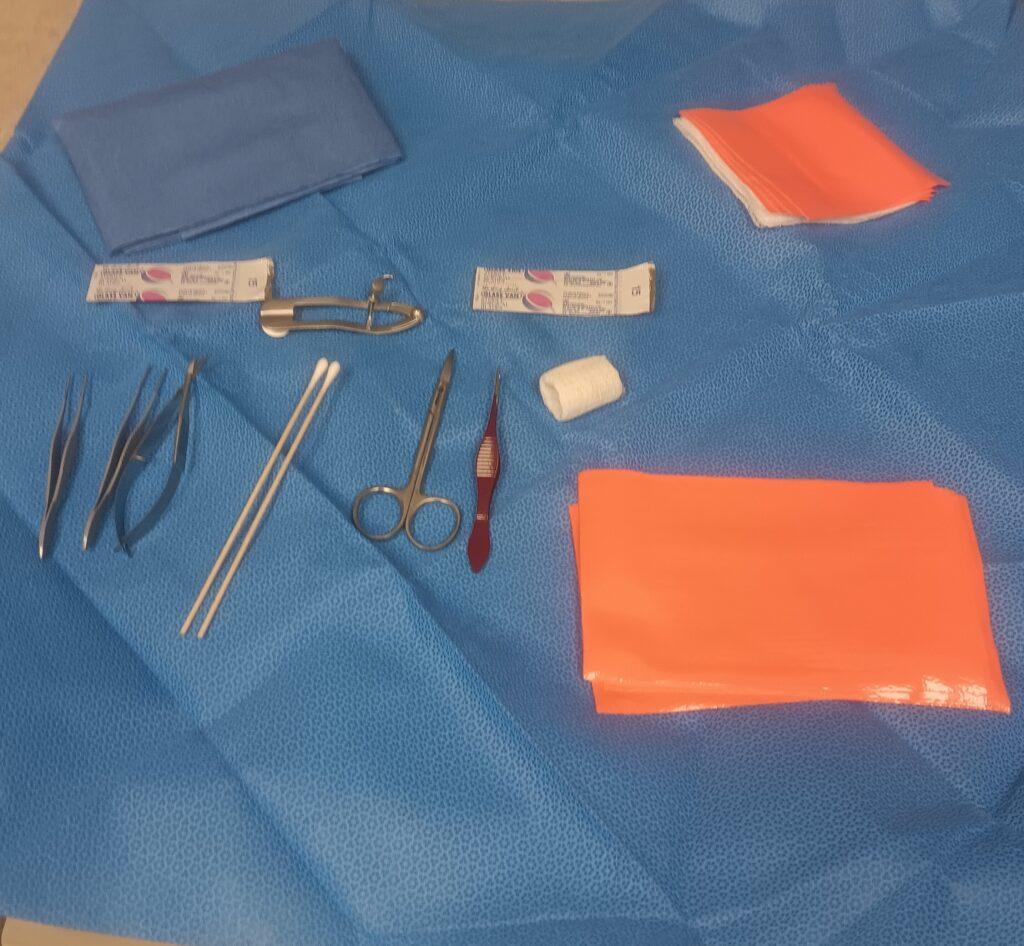

The eye bank staffer who went to the Loveland hospital to receive Bashaw’s donation – one of about 2,400 others they consider accepting for donation every year – had already spent six months learning to use the contents of a retrieval kit containing forceps, tweezers, scoring and cutting tools, an eyelid clamp, and a cloth to create a sterile field.

The collection process takes about 90 minutes and leaves the donor’s eyes looking as they had before, said Staci Terrin, technical manager of the eye bank, during a recent tour of the 5,500-square-foot facility.

Like other donations, the dome-shaped clear tissues would then have been taken from the hospital where Bashaw had received care – in an ice-filled container – to the eye bank to be placed in a refrigerator kept at a temperature of between 35.6 and 46.4 degrees Fahrenheit, ready for when a transplant surgeon called, according to Terrin.

Once the donations come in, a rigorous testing process begins to determine if the corneas can be transplanted into a living person, a process regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Those needing a cornea transplant include a person whose cornea got damaged during laser eye surgery, from an eye injury, viral infection or the disease keratoconus. A damaged cornea can cause blindness, haloed or blurred vision, or a sense that there’s something in one’s eye. Every year, thousands of people receive corneal transplants from about 70,000 donated corneas nationwide, if they are approved, according to Puente, who said the need for corneal donation exceeds supply.

Alisha wasn’t sure her dad’s would be approved for transplant.

“My dad had problems with his eyes,” she said. “He had glaucoma, and he had some stuff going on from diabetes.” So she was happy to hear they were usable and gifted to two different recipients. Later, she received their approval to get their contact information from the eye bank. She wrote them, both in Southern Colorado. One wrote back. “They were very kind. They were very sweet. They were just very grateful, but also said, ‘Thank you so much for reaching out. I want you to know your parent was honored in this.’”

In each of the past three years, about 2,400 people donated their corneas at Rocky Mountain Lions Eye Bank. But the majority were turned down for transplants. (The eye bank says it uses ones denied for transplant for research, but other facilities may discard corneas rejected for transplant, according to Puente and others.)

For example, of the 2,305 people offering corneas for donation last year, nearly all donated corneal tissue from both eyes, meaning there were about 4,600 cornea tissues collected. Of those, about 1,900 were considered acceptable for donation to a human recipient, according to the eye bank. Once approved, over 90 percent of corneas are transplanted successfully into the eyes of the recipients and restore or improve sight.

Corneas from men who have had sex with men in the previous five years are rejected during a screening process with the donor’s family and care providers, which often total a dozen contacts who provide details on the person’s life, according to Terrin. Other reasons for rejection include having a dementia diagnosis, because that disease is also suspected to be transmittable through cornea tissue – as well as diagnoses of other diseases, Terrin said.

The FDA restricts corneal donations from men who have had sex with men in the previous five years because of the administration’s concern of possible transmission of HIV through corneal tissue.

“The FDA routinely reviews approaches regarding donor screening and testing for donors of human cells, tissues, or cellular or tissue-based products (HCT/Ps) to determine what changes, if any, are appropriate based on technological and evolving scientific knowledge,” an FDA spokesperson said in an emailed statement in June. “This process must be data-driven, so the agency cannot speculate on any changes that may or may not occur in the future … Should there be any changes to HCT/P donor screening or testing recommendations, they will be communicated through FDA-issued guidance.”

The FDA’s position is based on a May 20, 1994, paper from the Centers for Disease Control entitled “Guidelines for Preventing Transmission of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Through Transplantation of Human Tissue and Organs.”

The “recommendations” section of the 26-page report points out that tissue and organ transplantation carries the risk of transmitting HIV, “emphasizing that HIV can be transmitted via transplanted organs and tissues … a negative test for HIV antibody does not guarantee that the donor is free of HIV infection ... Therefore, organs and tissue must not be transplanted from persons who may have engaged in activities that placed them at increased risk for HIV infection.”

The spokesperson for the FDA elaborated: “While the absolute risk transmission of HIV due to ophthalmic surgical procedures appears to be remote, there are still relative risks. The FDA’s guidance titled, “Guidance for Industry: Eligibility Determination for Donors of Human Cells, Tissues, and Cellular and Tissue-Based Products (HCT/Ps) includes screening for HIV risk factors and conditions, such as men who have sex with men (MSM).”

That 70-page FDA report was published in 2007. A portion of the “Donor Testing: General” chapter states: “[Y]ou should determine to be ineligible any potential donor who exhibits one or more of the following examples of physical evidence of relevant communicable disease or high-risk behavior associated with these diseases:”

Puente said the paper the FDA relies on came out when there were no tests to quickly detect HIV.

“Now, all corneal donors are required to have three separate HIV tests performed on them that weren't even available on May 20th, 1994,” he said. “Those tests are reliable within days of someone being exposed to HIV. So I would encourage (the FDA) to recognize that we live in a completely different world, that we have medical advances that were unthinkable on May 20, 1994, and they should base the current guidelines on the technology that we’re using in 2024.”

In response to a follow-up email asking why the FDA is relying on a 30-year-old paper instead of more current data and research on the topic, the spokesperson repeated portions of the administration’s initial response.

A contradiction Puente points out with the FDA’s policy is that it does allow men who have sex with men to donate organs including hearts, lungs, kidneys and livers – but it draws the line at corneas, despite no evidence of HIV ever having been transmitted through corneal tissue, he said.

“I think their justification has been that heart transplants or lung transplants or kidney transplants are immediately life-saving, so they were willing to take a little bit more risk, but if someone is blind and could have their blindness cured, they would rather the person be blind than have the increased risk,” he said.

As Puente continues to advocate for a change in the FDA’s corneal transplant policy, Alisha Bashaw celebrates the fact that her parents were donors. She said that six weeks after her father died, in 2016, her mother Sherri Bashaw, died after a long illness. She was 65 and had been married to Bashaw for 39 years, both working as science teachers. Alisha was again able to arrange for her mother’s corneas to be donated; this time the recipients were two people in Germany, one of whom also responded with gratitude when she reached out to see how the transplant worked out.

“I felt really grateful that she was able to give something that was also very reflective of who they were,” Alisha Bashaw said. “I mean, it’s a mixed bag: It’s really sad; your person is gone, and it’s also really beautiful that she can gift in death, and live on in some way through that donation.”

Puente would argue men who have sex with men are deprived of that gesture. But he said the issue isn’t just the benefit to the donor, but the restoration of sight, which, due to corneal shortage, many people don’t get.

“There’s an enormous need for corneas,” he said, citing a study by the Journal of the American Medical Association that found that for every one cornea donated, seventy people are waiting for a corneal donation. “There are millions of people across the world who are going to die blind because they never get a cornea.”