Nestled high in the Colorado Rockies, the annual MARBLE/marble Stone Carving Symposium has drawn sculptors, both professional and aspiring, for decades.

The symposium’s hometown of Marble gets its name from the historic Yule Marble quarry that started operation there in the late 19th century. The area’s signature white stone — which lawmakers named Colorado’s official state rock — has been used for such illustrious works as the face of the Lincoln Memorial and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington Cemetery.

The symposium's roots trace back to a chance encounter in 1977.

"I was invited to watch three sculptors, Scott Owens, Greg Tonozzi and Frank Swanson, carving from using one compressor over the river at Marble,” recalled founder Madeline Wiener. “But I didn't really want to watch. I wanted to do it too. So that planted the seed."

It took around a decade for that seed to germinate, but eventually, Wiener's passion and determination led her to take a leap of faith. She talked to the director of the Art Students League of Denver about offering a workshop in Marble and they connected her with a family that had land, and extra blocks of stone sitting around for them to use.

"And lo and behold,” said Weiner, “this is our 35th year. So 34 years later, here we are still doing it."

What began as a modest workshop has blossomed into a vibrant annual community that draws artists from all walks of life. For both instructors and students, the symposium's enduring appeal lies in its unique blend of natural beauty, artistic challenge and communal spirit.

For returning participant Eric Trenbath, the weeklong experience is both humbling and transformative. And it can be a bit nerve-wracking too, at least the first time.

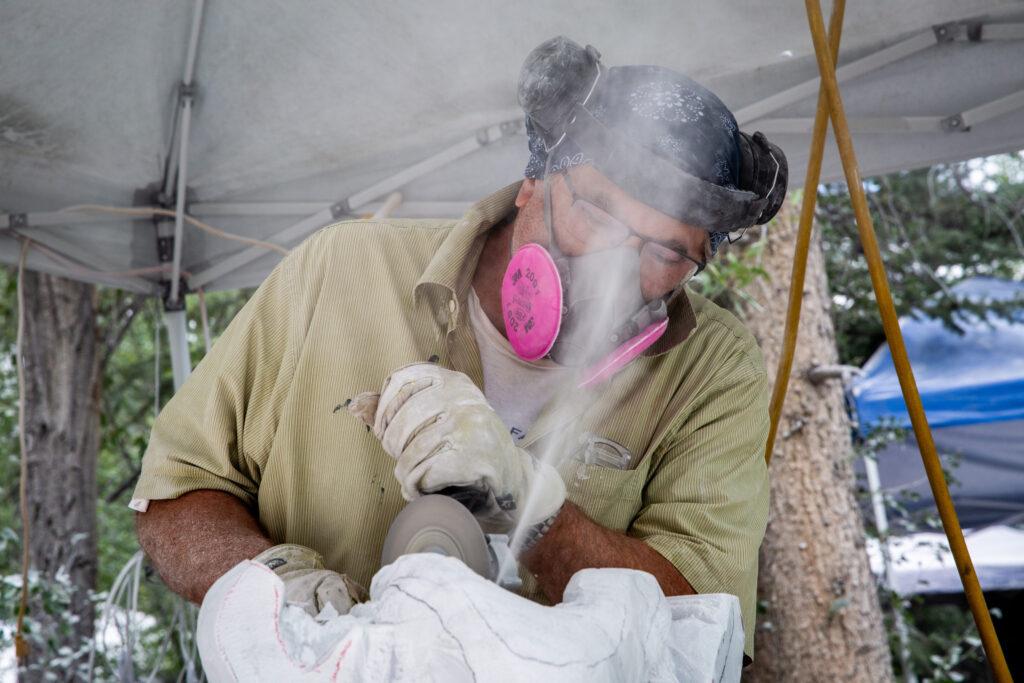

“You've got a giant chunk of rock and you think, ‘Oh my gosh, I've got to come out of here with a finished sculpture,’” he said.

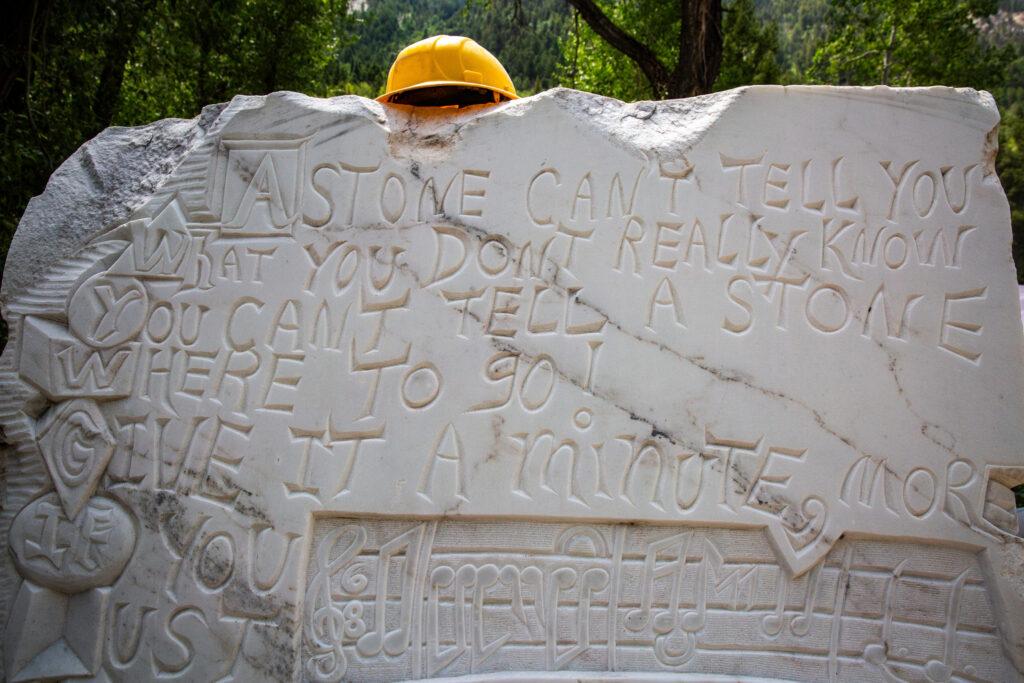

But he said participants quickly learn it’s the process that’s important, not the outcome. “You don't come out of here thinking you're going to have a masterpiece. You come in here learning to carve, learning to interact with the stone, learning to interact with the people and interacting with the environment."

Instructor Alan Brown says part of the joy of the symposium is that it attracts artists of all levels and ages, from college students to retirees in their seventies and eighties.

"Some of them are professional artists and carvers and are very experienced. And we also get people who have very limited experience in stone carving, or even in art, that are just trying to broaden their horizons,” Brown said.

A family passion

An ethos of welcome is central to the Marble Symposium’s spirit of openness and shared learning. Weiner's son, Joshua, who grew up immersed in this environment, notes that stone carving, like a lot of industries, has historically been pretty secretive. But his mother wanted to open the door for all.

“She shared everything that she knew and inspired other people to do the same,’ said Joshua Weiner. “And it really cultivates this space where people come with their skillset and even if they don't know anything in stone, they tend to have something that they're able to share here."

These days Joshua Wiener works alongside his mother to run the Marble Symposium, a natural progression, he said, since he grew up around it.

“My mother had a stone studio in our garage when I was really little and I would go out there and watch these stones transform into these incredible figures doing these really elegant moves. And that seemed really interesting to me. But I think the thing that really drew me in was the community.”

Weiner started out her career as a painter but said she struggled with color.

“Everything turned to earth tones and mud,” she recalled. It was a painting teacher who set her on a different path, by noticing the effect that her first forays into stone-carving had on her.

“When he saw me come up all excited with all my little dusty clothes and I was just so turned on by carving, he said, ‘That's it. I think you found yourself.’ And I am still finding myself, but at least I found what I love to do.”

Madeline Weiner’s creations focus on flowing, abstract figures. Many of her most prominent public works are ‘bench figures,’ crafted to invite people not just to look, but to take a seat and feel the texture of the rock. Her sculptures can be found along the Front Range, including in front of Colorado’s Supreme Court building and at the Denver Botanic Gardens, and around the country.

Weiner said she was raised to be ladylike, which came into conflict with her artistic passion. Working as a stone carver just challenged her to stretch even further.

“In a man's world, I had to prove my femininity (and) that I was up to all of it. No, I can't lift certain things that a guy standing next to me might have the strength to.” But rather than letting herself be intimidated, Madeline Weiner taught herself to preserve.

For many participants, the Marble Symposium has become more than just an annual event; it's a transformative experience that resonates long after the last chisel has been put down. Mike Schultz from Rico, Colorado, summed up the week as an amazing experience — "It's playful. It's just relaxing. Very soothing to the soul, I'd say"

Participants say the Marble Symposium's lasting legacy isn’t actually the sculptures created each year. It is in the bonds formed between artists, showcasing art's ability to unite, challenge, and inspire. That is what continues to draw artists and enthusiasts from around the world, all eager to be part of this community built of stone, skill and soul in the heart of the Rockies.