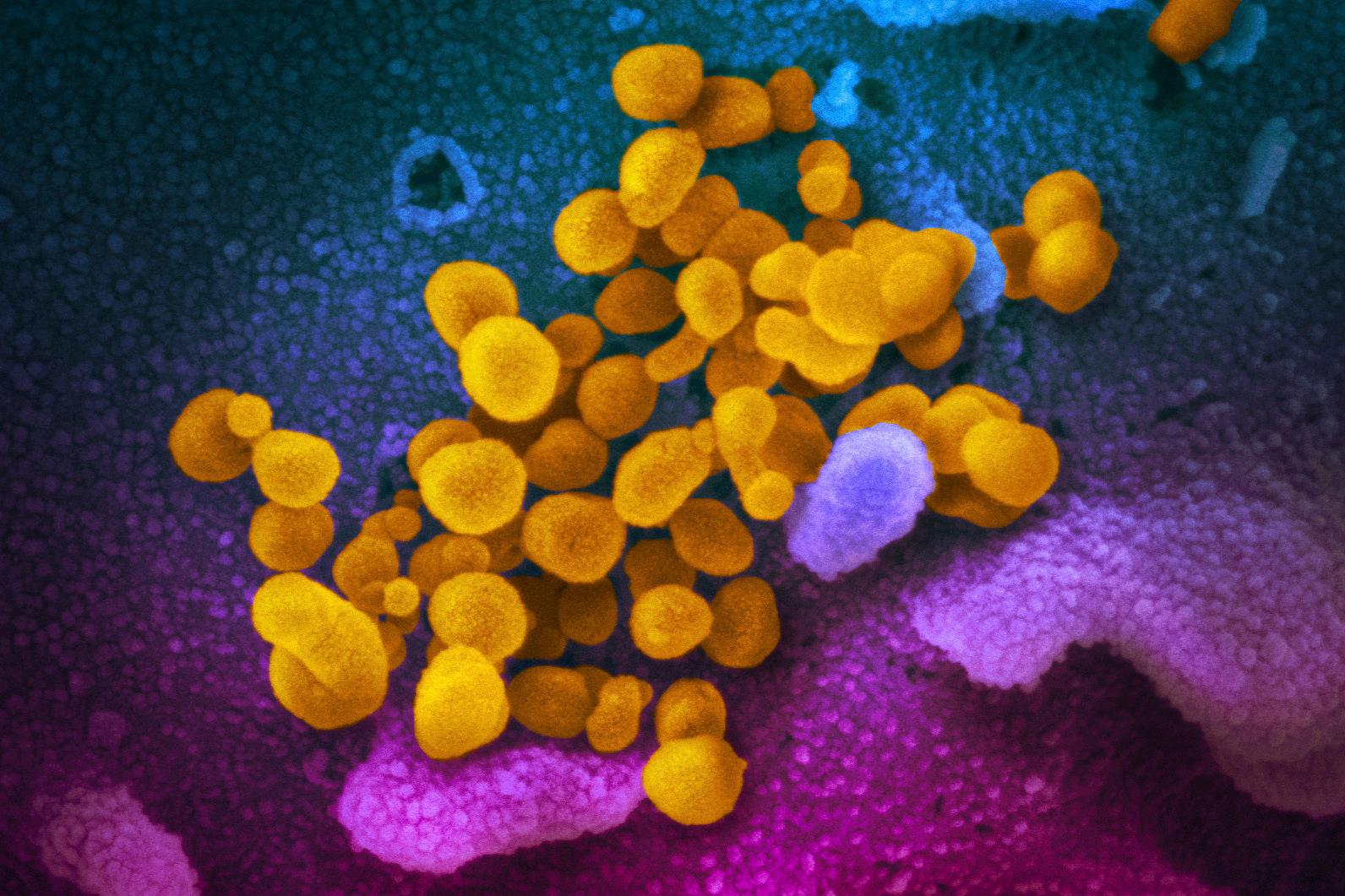

A new University of Colorado Boulder study found proteins that stick around long after a COVID-19 infection may help explain part of the puzzle of what’s driving neurological changes of long COVID.

Nearly five years since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, researchers are learning more about the condition which has caused millions of Americans to struggle with lingering symptoms like brain fog and intense fatigue.

These proteins can cause a big drop in levels of cortisol, an essential hormone that affects nearly every organ or tissue and plays a key role in things like energy production, regulating stress and suppressing inflammation. The proteins can also cause inflammation in the nervous system and trigger immune cells to react strongly when another stressor hits, according to animal research.

Earlier research showed proteins shed by the virus that causes COVID-19 to stay in the blood as long as a year post-infection, even being found in the brains of long-COVID patients who died, according to a press release from CU Boulder.

Researchers injected the spinal fluid of rats with the S1 antigen, a smaller part of the famous spike protein of the COVID-19 virus. They examined a number of inflammatory reactions in the brains and looked at the effect on behavior and physiology.

After a week, levels of corticosterone, the rat equivalent to cortisol in humans, dropped sharply, by 31 percent, in the hippocampus of rats exposed to the protein. That area of the brain is linked with memory, decision making and learning. After nine days, levels fell even more, 37 percent.

“Cortisol has so many beneficial properties that if it is reduced it can have a host of negative consequences,” said Matt Frank, a senior research associate with the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience at CU Boulder, in the release.

In a second experiment, researchers added an immune stressor, a weakened bacteria. They exposed different groups of rats to the bacteria and tracked their heart rate, temperature and behavior, plus the reaction by immune cells in the brain.

“Does the protein then change the brain in a way that makes it vulnerable to subsequent stressors or infection?” asked Frank, in an interview with CPR News. Corticosterone acts like a brake on the immune system. “If you take away that brake, then the immune system then becomes maybe more responsive to subsequent stressors.”

The rats previously exposed to the S1 protein responded much more strongly to the stressor, with “more pronounced changes in eating, drinking, behavior, core body temperature and heart rate, more neuroinflammation and stronger activation of glial cells,” according to the release.

“We show for the first time that exposure to antigens left behind by this virus can actually change the immune response in the brain so that it overreacts to subsequent stressors or infection,” Frank said.

He said more research is needed and noted humans obviously differ from rats. But this research, combined with more being done around the globe, could help scientists better understand the neurobiology of long COVID, and potentially develop medications and treatments someday.

Cortisol is key for humans to generate energy, for everyday activities and also to exercise.

“So I really believe that this could be playing a role in the fatigue symptoms that most long COVID patients describe,” he said. “And of course, cortisol also plays a role in learning and memory. And so if this has been altered in some way in the brain, then it could be affecting how you're able to learn or memorize.”

The study, funded by the PolyBio Research Foundation, was published this week in the journal Brain Behavior and Immunity.

More than 700,000 Coloradans may have been affected by long COVID, either still struggling with symptoms or having recovered.

That number comes from the state’s 2023 report on long COVID. It stated that about one in five people affected had severe symptoms that “greatly reduce their ability to carry out day-to-day activities.” About 5 percent of U.S. adults said they currently have long COVID, according to a U.S. Census Bureau survey.