For a time, Tokio Ueyama painted in Colorado. Like many artists in the Southwest, he was inspired by landscapes and resilient people.

The difference is that Ueyama was incarcerated in Colorado, along with thousands of others of Japanese ancestry at Camp Amache in the southeastern corner of the state during World War II.

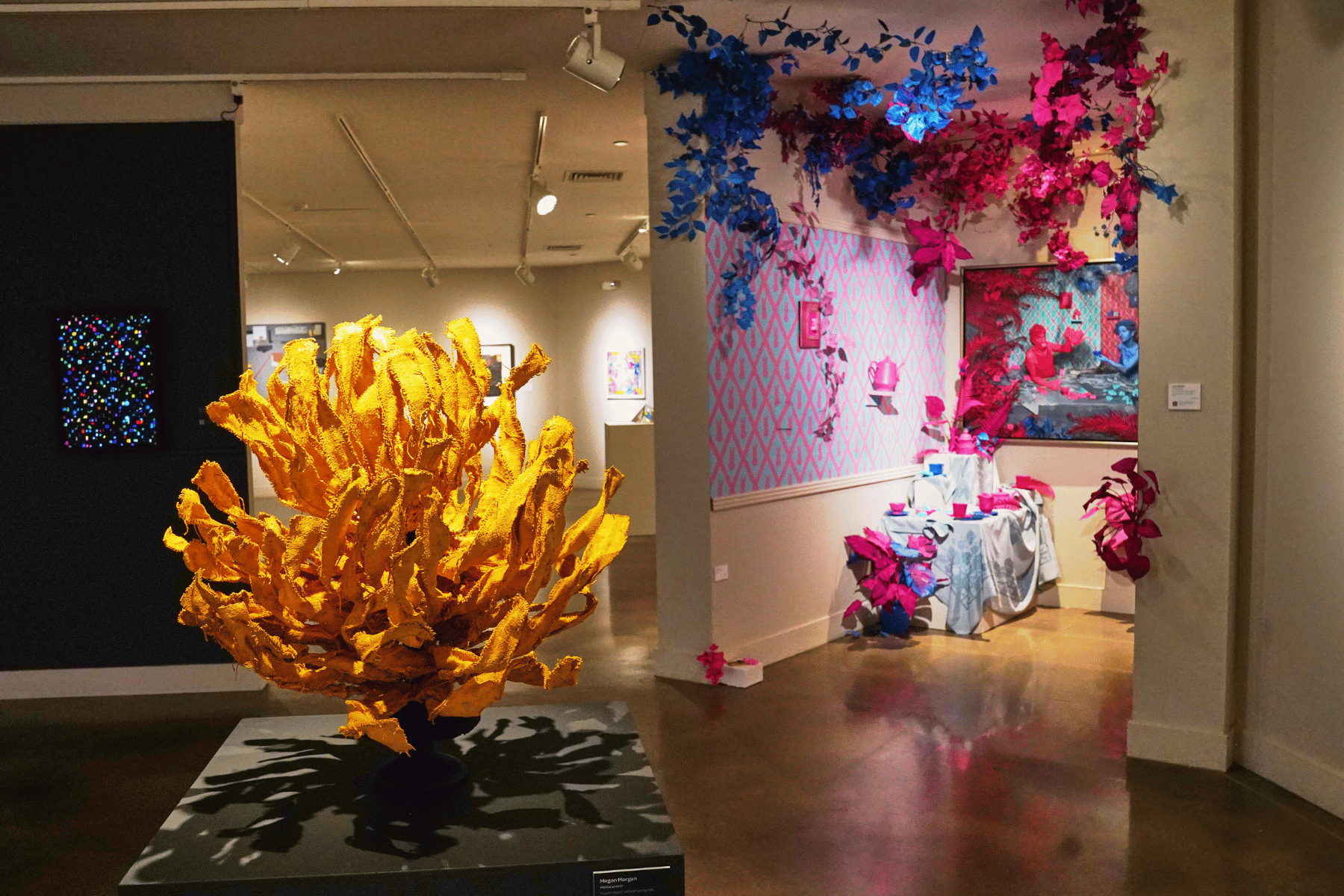

A new exhibition of his work, including paintings of the prison camp and its people, is on display at the Denver Art Museum through next spring. The Life and Art of Tokio Ueyama is a collection of more than 40 of his paintings.

Ueyama was born in Japan and moved to the United States in 1908 when he was 18 years old. He was well known in West Coast art circles and traveled widely, meeting artists like Diego Rivera in Mexico.

From 1942 to 1945, Ueyama and his wife were forcibly imprisoned at Amache, where he taught art classes, and managed to find beauty in the indefinite and harsh conditions of the camp. He died less than 10 years after he was released in 1945 at the end of World War II.

JR Henneman directs the Petrie Institute of Western American Art at the Denver Art Museum and curated the exhibit. She spoke with Colorado Matters senior host Ryan Warner.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity

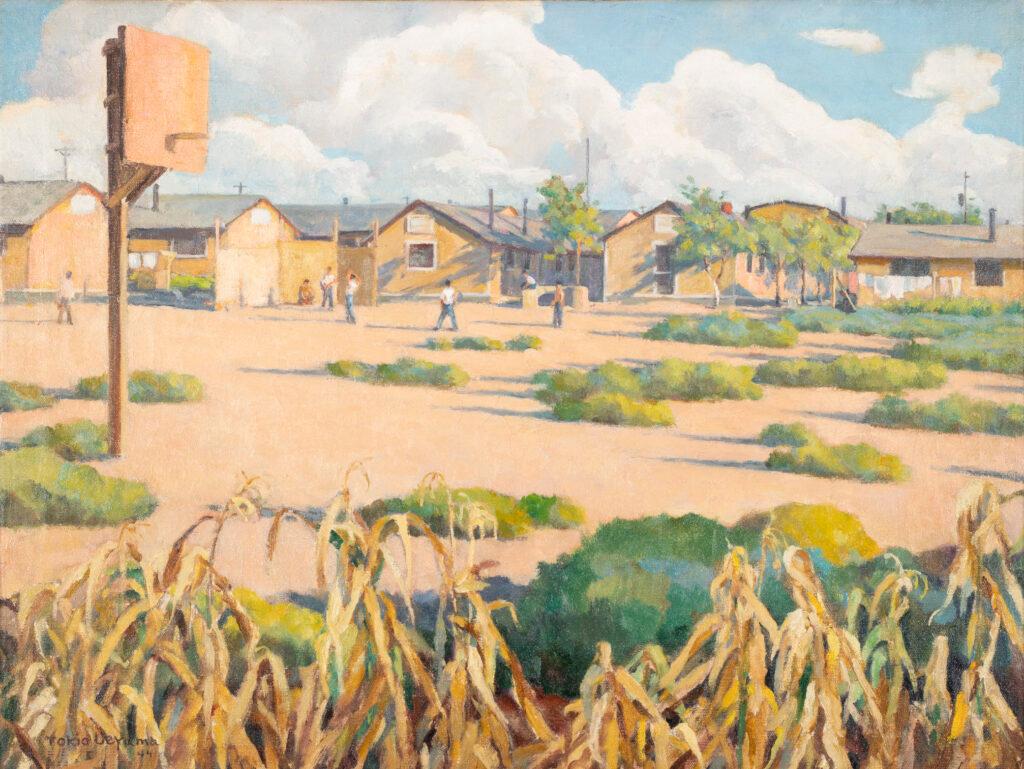

Ryan Warner: I want to start with a painting of barracks and basketball hoops at Amache. I'm struck by both how bleak it is and yet somehow soft and even lovingly painted thunderheads in the background, corn stalks in the foreground. What do you think we can glean from this image?

JR Henneman: This painting tells us a lot about the climate and the feel of Southeast Colorado where Amache is located. You can see how dry it is based on the hues, the yellows, the warm browns, reds. Of course, the building clouds allude to the vast sky on the Eastern Plains and the many storms that build. But what we see is a scene of everyday life. We see the barracks, which were hastily constructed, and we see people in white T-shirts and jeans hanging out in the sun. The shadows are long, so it might be later in the day, probably the afternoon since that's when the storms tend to build.

Warner: Yeah, if a painting can make you feel the heat, this does a good job of it.

Henneman: I think so. Even the implied crunch of those aging corn stalks in the foreground give you a sense of the time of year, but also that the sense of dryness and austerity. Those corn stalks could be part of the larger agricultural program at Amache, or they could represent an individual's victory garden. Many people grew their own victory gardens at Amache. And you see this basketball hoop and it's created completely from found materials. So there was very little material culture or comfort at Amache. The Amachians created what they could to make life livable, and that included their own victory gardens. That also included pastimes, ways literally to pass the time since there was no known end to this time of incarceration.

Warner: How much was Ueyama's painting to pass the time?

Henneman: I think it was a really important component of passing the time, but more than that, Ueyama was a professional artist. He had spent decades building a career as a fine painter, and so while being forcibly and unjustly incarcerated at Amache ruptured the career he had built, it did not keep him from painting. This was not only a way to pass the time, but a fundamental part of who he was as a human being.

Warner: Let's talk about his training. Let's talk about where painting brought him all over the world and meeting some rather well-known figures in the art world.

Henneman: He moved to the United States in 1908, around the age of 18 after living in Japan for his younger life. He studied a four-year painter's degree at the University of Southern California before then going to the most prestigious and well-established art academy in the United States, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts based in Philadelphia. There he studied a rigorous curriculum of what we would call academic training, studies from classical sculptures, from the human body, lessons in color, lessons in perspective. And his work was accomplished enough that he was awarded a scholarship to spend three months in Spain, in Italy, and in France.

After the Pennsylvania Academy, he came back to Los Angeles, which is where he made his home in the neighborhood called Little Tokyo in downtown LA and co-founded an art group called The Shakudosha, which exhibited each other's works and also brought in other artists to exhibit in Little Tokyo. Soon after his return to Los Angeles, he continued traveling. He went to Mexico for a summer in 1925, specifically to study the work of Diego Rivera, the great muralist. And while there, he listened to a lecture by Diego and also managed to spend time with the artist and through a translator, had a conversation with him. We know based on an existing address book that he also met the artists, Jean Charlot, Miguel Covarrubias. And we believe that he also met the American photographer Edward Weston, while in Mexico.

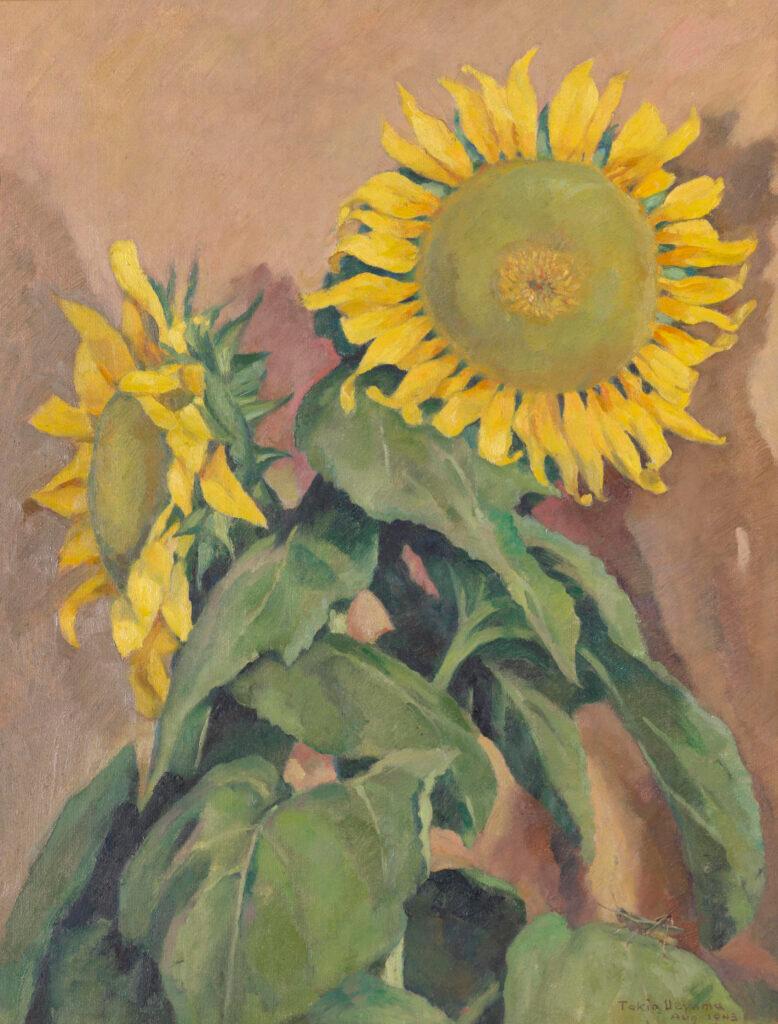

Warner: So just behind you, I think that's a sunflower. There is another painting with a gourd, some corn, a hat, and a lantern, again, with his incredible use of light. And then in between the two still lifes I've just described, you've got a kind of pastoral scene dated 1945. How did he have access while at Amache to the tools of painting?

Henneman: Amachians, although unjustly incarcerated, had access to any kind of goods you could obtain through a mail order catalog. They were restrained behind barbed wire fences. However, there was a post office at Amache so they could receive goods and services through the mail. Amachians also created their own co-op store on site that was so well-stocked that citizens from Greater Prowers County where Amache is located would come to Amache to shop. Amachians could receive permission to leave the borders of the camp, and in so doing could then travel to Grenada and beyond, even to Denver to work, and would also have had access to goods and services there. And of course, they would've had friends and family on the outside or out living elsewhere who might've had access to materials, including art materials. The access to materials would not have been as challenging, I believe, as building the wealth to afford them.

Because the whole process of forcibly relocating Japanese Americans from the West Coast meant that many people left their homes and their businesses, all of their worldly belongings except for what they could carry and did not get that back. Now in the case of the Ueyama's, Tokio and his wife Suye, they had allies on the outside. Their friends and landlords, Mr. and Mrs. John Wilson who lived in Los Angeles and who preserved their property while they were incarcerated. So this exhibit exists only because of Mr. and Mrs. Wilson's allyship in their simple human kindness of preserving the Ueyama's property so that years later, the artworks and the archives, the photograph albums and newspaper clippings, the address books, the diaries, these still exist because they were protected. And that allows us to steal a larger story of Ueyama's life and work both before and after Amache.

Warner: Why don't you walk us to a portrait? He's just so good at it all.

Henneman: He's a very accomplished artist. There's a wonderful portrait from 1928 of his wife Suye. The portrait is called “Portrait in Black” because she is dressed in a black cloche hat, in a black fur coat.

Warner: Okay. This is a fur coat. He has conveyed that beautifully.

Henneman: And it's a very poised, I would say, traditional portrait. If you notice her face, she's just glowing. It's a glowing portrait of a classy, modern woman who happens to be Japanese American. And who the same year marries the artist Tokio Ueyama.

Warner: Ah. They were married the year he painted this. Do you think maybe this was part of the courtship?

Henneman: Maybe. It’s lovely to think of it that way.

Warner: It is a lovely thing to think about, and this goes back to the word I used earlier, which is loving. There's a sense, I mean, even in the miserable confines of Amache, there's a sense of, I don't know if it's his world view or his kind eye. Does that make sense?

Henneman: Yeah, that's really lovely actually. He was an artist motivated by a search for beauty. So he wasn't commenting on the realities of Amache, the hardships of Amache necessarily, or if he is, they're kind of tucked into a more beautiful translation of that space. And I think it's because it was important for him to find the beauty in what he was observing and to translate that for us, the viewers.

Warner: Indeed, there are two self-portraits in the show. One of a young confident artist before the war, then one later in life painted at Amache. In that one he's mustachioed, he's quite comely. He's so brilliant at painting skin, I guess in this case, his own skin and the light. Where should we consider him in the artistic canon? Is this someone who should be better known?

Henneman: Absolutely. Like many artists of Asian descent, the American art canon, our American art histories do not always represent communities of color. And in this case, we see an artist whose work is extraordinary both emotionally and technically. And we see an artist who is leveraging his skills and his eye to create viewpoints into an experience that was unique to Japanese Americans from the West Coast. There's not only an art historical rationale for including artists like Ueyama in the canon. There's also an important historical rationale, not just the Amache story, but the contributions of people of Asian descent in the United States and in the greater American West. This is a history that is frequently not told to the degree or complexity perhaps, that it perhaps should be.

Warner: His life after Amache was not long. I think he had about a decade, right?

Henneman: So he and Suye left Amache in 1945, and he died in 1954. But remember he was born in 1889, so he was in his 60s when he passed away. When he was at Amache, he was an older established artist.

Warner: I think I'm left with the impression after our conversation and after looking at the work and considering the history of Amache, I'm reminded of how Amachians were robbed of potential. What might have been if his talents were allowed to remain unleashed, unencumbered.

Henneman: I think that's true, and we need to acknowledge the ways in which the Amachians demonstrated their resilience and their creativity and their productivity. So in the case of Ueyama, while Amache ruptured his career, it didn't stop him from painting. And in fact, he worked for the War Relocation Authority, which is the authority that managed all of the 10 WRA camps in the United States as part of the adult education program to teach adult students how to draw and paint. So at Amache, he taught three days a week, and in his own estimation, he thought he had about 150 students over the course of time, many of whom had not dabbled in the arts before or had, and then because of their real lives had to leave art behind. And so while Amache absolutely ruptured people's lives and in many cases impoverished them, it also provided opportunities for people like Ueyama to teach skills like art making that ended up being, I believe, a crucial lifeline at Amache for reasserting their own humanity, their own creativity for passing the time through the arts in a way that built community when community had been ruptured. And so, yes, there is rupturing, but there is also building. And it's that complexity of experience and returning agency to Amachians that is a critical component of this history as well.