Groups hoping to reelect former president Donald Trump spent hundreds of millions of dollars on ads that tied his opponent to her support for trans people. Swing-state voters ostensibly were persuaded by slogans like, “Kamala is for they/them; President Trump is for you.” Trump vowed to roll back gains and protections for the trans community.

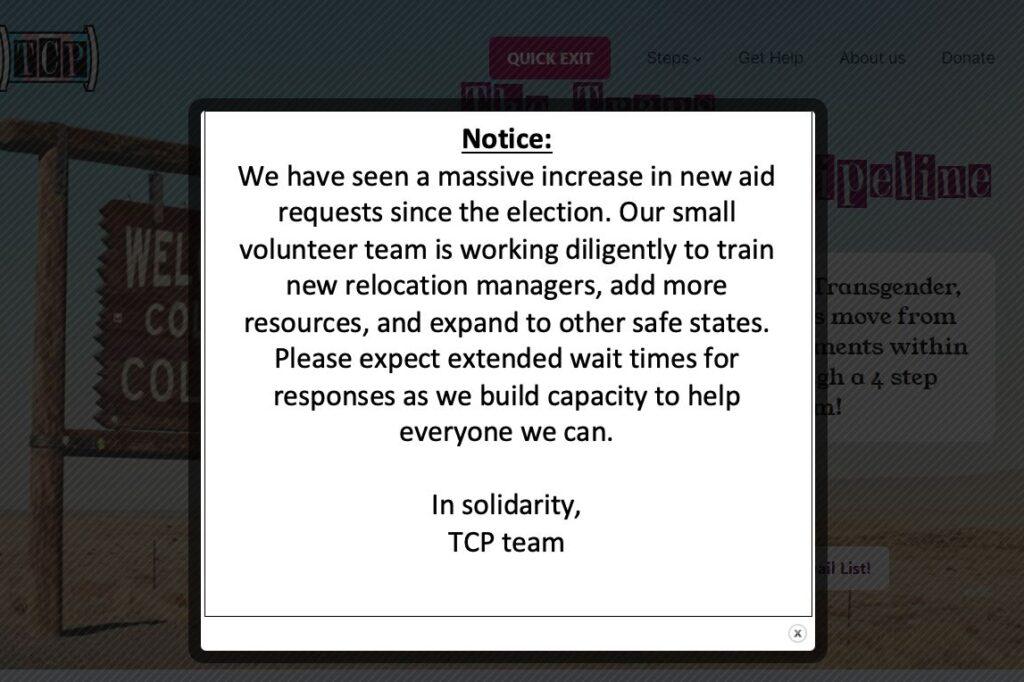

As soon as the race was called, Trans Continental Pipeline, a queer relocation nonprofit in Colorado, was flooded with requests from trans people looking to flee to Colorado from states where they are more vulnerable.

TCP’s Executive Director Keira Richards spoke with Senior Host of Colorado Matters Ryan Warner.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity

Ryan Warner: Help us understand the fear a trans person who’s contacting you now is experiencing and why.

Keira Richards: It's twofold. We're already seeing major state-level attacks on access to medical care and the protections most people expect under law, such as the ability to get an apartment, the ability to find employment. These protections are already being stripped away in over half of U.S. states right now.

Warner: So that was already in the background.

Richards: Already happening. There were 617 anti-trans and queer bills put forth in state legislatures last legislative session. We can only assume that’s going to continue to grow year over year, especially compounding with the new risks at the federal level. And that's what people are worried about now. We don't really know what's going to happen at the federal level, but all states that don't have explicit protections like Colorado will default to whatever the federal rulings are, potentially putting trans people at risk.

Warner: I think any number of people wonder what the next Trump administration will hold, what promises will be kept, what was perhaps bravado. What did you hear from the Trump campaign leading up to the election about trans people?

Richards: It was a bit hard to read for me being a trans person, but I saw a lot of attacks on trans women playing women's sports; and especially children — their access to gender-affirming care, even if that's just therapeutic and mental health support; attacks on hormone replacement therapy (HRT); and attacks on the very existence of trans people — in that they could define us out of law — gender only being recognized by the gender assigned at birth. That would essentially legislate transgender people out of existence.

Warner: Geographically, where are the bulk of requests coming from, and is Colorado the only state you help them move to?

Richards: At the moment, we are the only state that we help people move to — given that we have developed what we call, “The welcome wagon resources” for Colorado — helping people get connected to things that they need once they get to town.

But the bulk of our transplants, as we call them, (another terrible pun, I'm so sorry,) but the bulk of our transplants are coming from Texas. Texas recently saw a rather creative attack in which their vital records agency is disallowing new changes to birth certificates and identification to reflect a person's gender. And there's actually been talk of, and I don't know if these have started off the top of my head, but reversion of documents that have already been changed, which would then put people at risk given that their identities — and just how they present in the world — will no longer match their documentation.

Warner: We can assume then that Colorado is among these safe harbor states. Do you want to speak to the landscape here that makes it a better destination for these trans folks than where they're currently living?

Richards: Absolutely. Colorado is referred to as a bit of a sanctuary state in that there are legislative protections that stop the persecution of doctors or therapists who help trans kids discover themselves, be who they want to be. There are protections for HRT providers. There are robust nondiscrimination laws, so that you can't be fired for being transgender in Colorado. And frankly, Colorado has a great track record of ignoring the federal government, which I think gives people a bit of faith in relocating here.

Warner: You talked about the “welcome wagon.” What does aid mean in this case? What do trans folks need who are considering a move to Colorado?

Richards: Most people we're seeing requests from, some have never even been to Colorado, but the vast majority don't have any family, friends, contacts or even knowledge of really what is in Colorado. So our goal is to help people get connected to community organizations or just social connection. But at a more basic level, getting connected to workforce centers, getting connected to local HRT providers, therapists.

Warner: Can you give us an example (obviously without divulging too much) of someone you helped relocate?

Richards: We've had easy cases where people are like,”‘I just can't figure out the logistics. I don't have any roommates.” We had one particularly heartwarming case where somebody from Oklahoma came out with their mom and just hung out with us for a bit. We met up with them through our peer network and went to a concert and just tried to show them around Denver and answer all their questions.

And then we get into the tricky ones. We've had cases of people that just ditched everything in Ohio and came to Colorado. We got a call from them saying, “We're going to be in Denver tonight. We used the rest of our money on a plane ticket and we need help.” And, of course, we did our best, but at that point, they're leaning on the already-strained homeless systems in Denver and Colorado in general. It's hard not being able to help everybody to the extent we want.

I'd say the particularly heart-wrenching cases are when we get in contact with the parents. I have lost count of the voicemails I've gotten from parents in Texas, Florida, Alabama saying, “I am terrified for my child. They are not doing well. They're having mental health struggles.” All of it is a direct result of their state legislature coming after them. And these parents just feel trapped because, I mean, that basic parental urge to help their kid as much as they can, but they just don't know what to do.

Warner: The range of cases you've described indicates this all-ages phenomenon.

Richards: Absolutely. I think the oldest person I've been in contact with was in their mid-70s, and I've had parents reach out about their 11-year-old. It is really all walks of life, all ages.

Warner: I wonder if there is some concern about the cost of living here. It strikes me that folks may be moving from places that are just cheaper.

Richards: Absolutely. We've had a lot of cases in which people are like, “My budget for a room in a house is about $400. I would like to be close to public transit.” And we have to have a very tough conversation. That is just not something you're likely to find in Denver. I do think that– especially from rural areas of Alabama, Tennessee, Texas, Mississippi, where we've been having these conversations — that people are very surprised about the cost-of-living difference.

Warner: One survey found 81% of transgender adults in the U.S. have thought about suicide. Trans people are also vulnerable to violence — four times more likely to experience assault. What are your concerns in that regard just in this new environment?

Richards: I think we can expect to see actions reflect the rhetoric. We can hope that given the more accepting nature of Coloradans and of Metro Denver, there won't be as many cases where people are feeling physically threatened. But it's certainly a difficult situation to say the least. I myself have had some rather colorful interactions — just given my public-facing role as a trans person running this organization. And I think we can expect to see those increase — assuming Trump continues his attacks on our community.

Warner: Your organization grew out of the dating app Tinder?

Richards: Yep. Tinder is, from what we've seen, one of the first places people go when they get to town because they're feeling lost and they want connection, and dating apps are built for connection. So we were seeing profiles of people being, like, “Hi, I just got to town and I don't know anyone.” And so we developed this sort of ad hoc network where we'd connect with them and reach out and be like, “All right, so what are you looking for?” And so we'd start this name-trading network where it's, like, “OK, you want to find the concert scene, talk to this person. You want to join roller derby, talk to this person.” And it worked pretty well for what it was basically just facilitating these social connections.

Warner: Your organization is spread thin right now. What does the scramble look like? How are you trying to meet this moment?

Richards: We're doing everything we can think of right now. We are working with organizers in other states with protections — such as Illinois and Minnesota — to get other chapters started. They essentially want to either work with us or copy off our homework.

Warner: And you're, like, “copy away!”

Richards: Yeah, absolutely. The more people we can get doing this work, the more people we can help. I mean, not everybody wants to move to Denver. Not everybody wants to move to Colorado. And so if we can build out this national network, everybody will be in a much better position.

Warner: So what do you need?

Richards: As crass as it may sound, we need donations and we need institutional support. We are a bunch of 20-somethings running a six-and-a-half-month-old nonprofit. We are doing our absolute best with essentially one hand tied behind our back — being that we are completely volunteer-run and everybody has day jobs.

The average cost of a cross-country move is, I believe, $4,600, Forbes said back in July. And just to meet the need we're facing, we need the finances and institutional support. We don't have full-time grant writers. We don't have full-time volunteer coordinators. So if we can get the big players in the queer nonprofit sphere in on this, everybody's lives will be much better.

Warner: Keira, how are you doing?

Richards: Personally?

Warner: Yeah.

Richards: It's been a rough week. I'm not going to lie. It's been a mad scramble trying to get everything put together as best we can. We're seeing an influx of requests. I got 250 since the election and we're just doing everything we can to catch up.